Top 5 Ways to Improve your Book’s Villain

Oliver Smuhar

Sunday, 15th September, 2019

A killer antagonist, whether it be a person who challenges the ideologies of your main character (MC) or something more psychological, a cure, an illness, or a decision, it can be the sticky glue that holds your fantasy epic, your emotional, slice of life drama, you mental hospital memoir together. However, it seems—especially on Wattpad—that antagonists are placed in last minute to give the main plot a little more drama; because who doesn’t love a bit of drama? Well, instead of talking about why you should read, I’ve collected five ways for you to improve your book’s antagonist.

1. Give them a backstory that influences the reasons for why they challenge your MC!

This is the most obvious and most overlooked aspect to an antagonist. Like seriously, why don’t writers put a little effort in exploring their baddies backstory? Take the 1990s tv miniseries, IT, seeing that at the time of writing, IT Chapter 2 (2019) just released. In the two parter, Tim Curry’s Pennywise is merely a scary clown until the last twenty minutes of the film when he becomes a giant spider. It’s proven in the first part, his version of Pennnywise is some sort of alien—but that’s it! That’s all you find out. He’s a scary clown, who likes to torment kids, I think there’s something to do with souls, which is really bizarre when you take in consideration Stephen King’s master piece, at over 440,000 words (La Yerba Mate 2016), book with the same name, IT.

(Image: Wong 2017)

Not only does King go into thorough detail about the court hearing that takes place before little Georgie’s death at the beginning of the book, the man explores the philosophical impact for the town and how they place a blind eye on Pennywise’s killings, he shows and tells his audience where Pennywise is from, why he chose Derry, the fictional town the book takes place in and why he murders children in the first place. And all these reasons, detailing his background, what his flaws are, challenge the protagonists all the way into their adulthood, until they finally defeat the clown of terror. It gives us, the audience, a reason to vouch for the heroes, but it also creates a more rewarding reason for the whole conflict, humanising the events that takes place with a killer clown from outer space and some kids from Derry.

2. Make the antagonist threatening through the five senses

I’m sure you’ve heard of the five senses before—sound, smell, touch, sight and taste. By themselves, they’re simplistic in nature, however, when composed together, a book can become enchanting, making its audience apart of the events that take place.

(Image: Geddes 2017)

Thus, an antagonist should manipulate these senses in challenging ways for the reader. They should give the MC goosebumps up their arms, have them smell of lingering death, a sickness, something hazardous like the top of the local dump or the bathrooms in the public toilets, and if the antagonist is an illness, it could taste mouldy, sad, toxic, things shouldn’t be okay when they’re present. Hearing their name needs to be a taboo, a word the protagonist hates or fears and maybe it’s what’s keeping them from giving up. With reference to the five senses, the antagonist will not only be more threatening, but it will make the reader have conflicting emotions towards them. The antagonist will be challenging for everyone involved, including us, the audience.

3. Don’t always make them the exact opposite of your MC

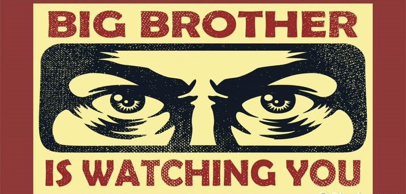

Light and darkness, fire and water, the good and the bad, these tropes of opposites have been around since the first antagonists described onto a page. Although, this form of development is extremely smooth, it does indeed challenge the MC as the antagonist is everything he/she is not, it doesn’t leave much space for deeper development of themes, can make your book/story more cliche and, if poorly executed, can bore your audience. Take the CW’s The Flash. In the first season, the MC the Flash is opposed by the Reverse Flash… It’s extremely on the nose and straight forward. They’re costumes are polar opposites as well, yet they have pretty much the same powers. Another example is in Transformers. Optimus Prime and Megatron are brothers; one of them wants to protect civilisation, while the other wants to annihilate civilisation. In hindsight, these two products are aimed towards younger children and teens to sell merchandise, it also creates a striking visual between good and evil, but what if the villain wasn’t an oppositional variation? Take Big Brother from George Orwell’s 1984.

(Image: Linzey 2013)

(Image: iceprincess7492 n.d.)

(Image: Hasbro 2008)

Most of Orwell’s stories are showing not telling, he uses the five senses like an addiction, showing his readers how something like governance, propaganda and restrictions on privacy and freedom can be an antagonist.

(Image: Pathania 2019)

Big Brother doesn’t even appear in the book, we have no idea what he looks like or whether he is dissimilar to Winston, the MC. You can barely relate the two and that’s what makes Big Brother more endearing. He’s not an opposite, yet he’s still opposes Winston’s dream of rebellion. Thus, linking back to having an antagonist that challenges your MC, it’s not because Big Brother is the opposite, but through his characteristics. This can be developed further through the Four Main Types of Epic Antagonists (Kieffer 2017).

4. The antagonist doesn’t have to be simply evil

Kristen Kieffer (2017) outlines that the evil type of antagonist is only one of four main characteristics your antagonist can have when challenging your MC. To summarise, the evil villain is in superhero, fantasy and sci-fi stories, it’s the person who wants to hurt others, get revenge and cause chaos (Kieffer 2017), but let’s analyse how the other types can help you write your own antagonist.

(Image: Acosta 2017)

The Every Day Antagonist:

This antagonist is more simple. Kieffer (2017) states that this type is much less of the marauding villain and are rather the people who oppose the MC’s main aim, culture, norms and ideologies. Most commonly used inside romances and contemporary stories, this character isn’t trying to blow up a city, they’re preferably attempting to achieve the same goal as the MC, discouraging the MC to reach a certain achievement they find dangerous or create emotional/physical barriers that hinder the storyline (Kieffer 2017). Example: The Evil Step Mother from Cinderella. This type of antagonist can be fantastic for story twists and changes for supporting characters, like the best friends revealing their true terrible intentions.

The Immoral Antagonist:

This isn’t just one single person or villain, Kieffer (2017) suggests that entire entities such as a government, an organisation or a social system can also be challenging oppositions to your MC. Similar to the evil type antagonist, these entities want to hurt the protagonist and the group they belong to, to attain either revenge, power or wealth. These are extremely popular in young adult fantasies and adventure books (Kieffer 2017). Example: A.W. from The Gifts of Life or WICKED from The Maze Runner. Standing up to The Man can allow your story to have an emotional prevail of good over the more mighty evil inside contemporary consumerism and themes revolving around propaganda, governance or human rights.

(Image: Villains Wiki n.d.)

(Image: The B-Team 2010)

The Internal Dilemma:

As I mentioned before, sometimes the most challenging opposition to a MC is something inside their inner selves. Kieffer (2017) mentions that this internal struggle is a central part to character driven stories—when an MC must confront their flaws, a regret or a fear to reach their aspirations. This is often times personified in the MC’s actions (Kieffer 2017). Example: Buzz Lightyears internal struggle about being a space marine or a toy. This can add a deeper layer to your story and can allow a new perspective on situations your audience may not be aware of, such as to see what is inside the mind of someone who has a mental illness.

5. Do what feels right in your story

Do what feels right by your characters. If one side character needs to get slain by the evil type antagonist you’ve created, then kill them off or if you need your antagonist to appear in-the-flesh officially halfway in the book, have them appear in the middle chapter. At the end of the day, if your antagonist opposes your MC, then you’ve already done an amazing job. If a deep backstory is unnecessary for your children’s book, then simplify it by providing reasons for your antagonist’s goals and why they juxtapose your MC’s own aspirations. If the internal dilemma is brought on by a diagnosis of cancer, then introduce the medical procedures and checkups that are used in the time of the book’s storyline, whether it is the nineteen hundreds or the twenty first century and show how this struggle has confronted your MC both in there day to day life and their interaction with others. As long as the antagonist, the villain, the clown, the evil, the normal, the person or organisation challenges your protagonist through the plot points that feel right with how you write, then they should uphold a firm footing and become a successful and great antagonist.

Citation

- Acosta, A. 2017, Whats your Stepmom Persona, Anna de Acosta.com, viewed 15 September 2019, (https://www.annadeacosta.com/blog/whats-your-stepmom-persona).

- Geddes, R. 2017, Exploring the Five Senses, weblog, Geddes, viewed 15 September 2019, (https://www.raymondgeddes.com/exploring-the-five-senses).

- Hasbro. 2008, Hasbro Transformers Animated The Battle Begins - Optimus Prime vs. Megatron, Amazon, viewed 15 September 2019, (https://www.amazon.com/Hasbro-Transformers-Animated-Battle-Begins/dp/B00126R01I).

- iceprincess7492. n.d., The Flash vs. Reverse Flash - Finale Poster, Fanpop post, Fanpop, viewed 15 September 2019, (http://www.fanpop.com/clubs/the-flash-cw/images/38470429/title/flash-vs-reverse-flash-finale-poster-photo).

- Kieffer, K. 2017, The Four Main Types of Epic Antagonists, well-storied, viewed September 14 2019, (https://www.well-storied.com/blog/the-four-main-types-of-epic-antagonists).

- La Yerba Mate. 2016, ‘What is your Stephen King word count,’ subreddit, reddit post, viewed 12 September 2019, (https://www.reddit.com/r/stephenking/comments/4gdklp/what_is_your_king_word_count).

- Linzey, C. 2013, Good Vs. Evil, The Bible Blotter, viewed 15 September 2019, (https://chrislinzey.com/2013/08/01/good-vs-evil).

- Pathania, A. 2019, How Relevant is George Orwell’s 1984 Today, DU Beat, Delhi, viewed 15 September 2019, (http://dubeat.com/2019/06/how-relevant-is-george-orwells-1984-today).

- The B-Team. 2010, Hidden Gems: Toy Story 2 (1999), weblog, What-does-he-know?, viewed 15 September 2019, (http://what-does-he-know.blogspot.com/2010/08/hidden-gems-toy-story-2-1999.html).

- Villains Wiki. n.d., WCKD, Fandom.com, viewed 15 September 2019, (https://villains.fandom.com/wiki/WCKD).

- Wong, A. 2017, ‘It’ Director Explains Difference Between Movie and TV Pennywise, Inverse, viewed 15 September 2019, (https://www.inverse.com/article/36140-stephen-king-it-pennywise-clown-film-tim-curry-1990s-movie-differences).